“EH Young is virtually forgotten yet her books perfectly capture the spirit of Bristol,” says local historian and author Kirsten Elliott, who, this month, takes a closer look at the city through the eyes of the best-selling novelist and remembers her legacy…

Ask people which writer they associate with Bristol and they might come up with Robert Louis Stephenson, Thomas Chatterton, Angela Carter or Helen Dunmore. EH Young is virtually forgotten yet her books perfectly capture the spirit of Bristol, and especially of Clifton.

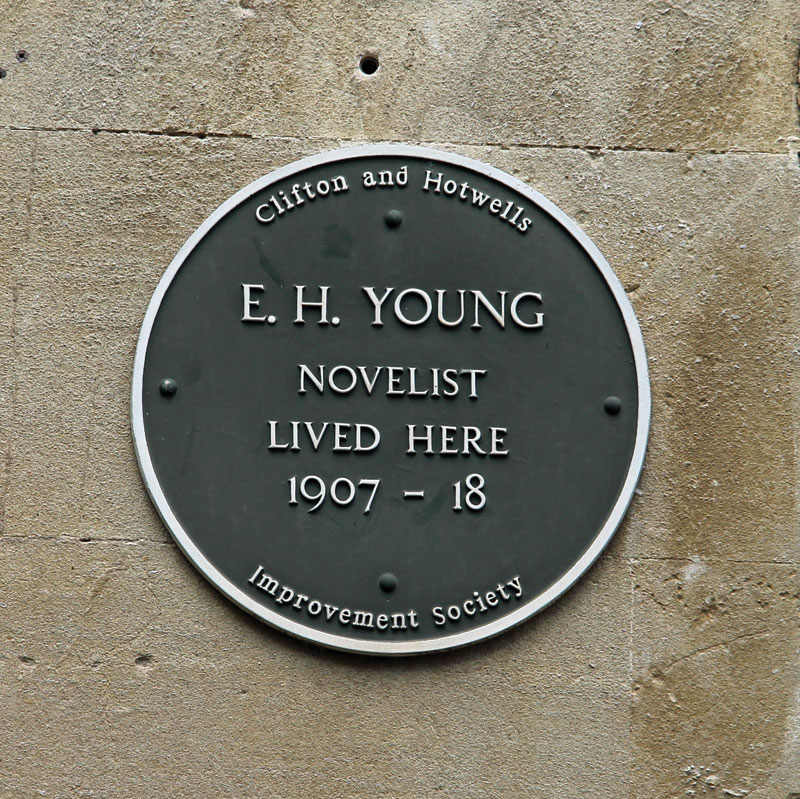

Emily Hilda Young first came to the city in 1902 as the wife of a Bristol solicitor, Arthur Daniell, living at 2 Saville Place. Here she was introduced to his old school friend, the headmaster of Alleyn’s School, Ralph Henderson. The three shared a love of rock-climbing. She was, in fact, an outstanding mountaineer, leading friends over a route in Snowdonia previously thought unclimbable.

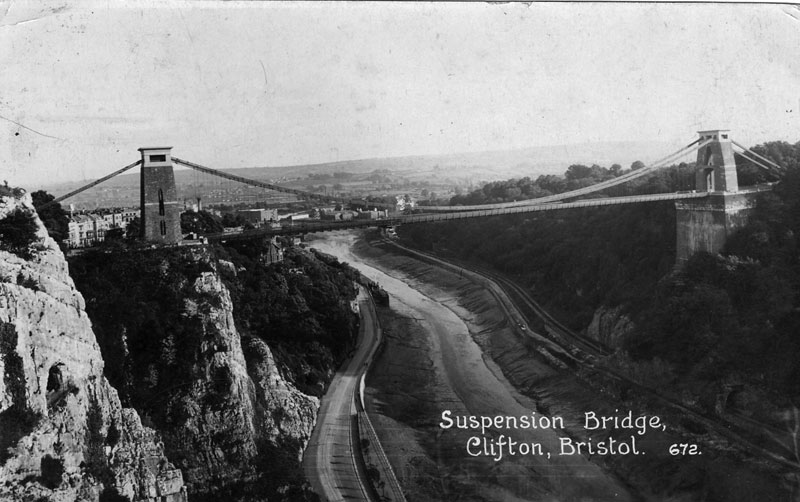

However, Henderson and Young developed a rather different passion, although if it was an extra-marital love affair, it was very discreet. In 1914, Daniell went off to war in France, while Emily worked in stables and at a munitions factory. Her life in Bristol was almost over, for in 1917 Daniell was killed in Ypres, Belgium during the Battle of Passchendaele. Emily went to live in an apparently amicable ménage à trios with Henderson and his wife, at Sydenham, in Croydon. She would never live in Bristol again, yet that brief space of 16 years was to be crucial, for she then began a series of books set in the city, which she called Radstowe. Clifton became Upper Radstowe and Whiteladies Road became Nunnery Road. Many other locations in the books, though, are elusive. Clifton Suspension Bridge was symbolic for EH Young, who referred to it as The Bridge, and it is central to the stories. The first of the Radstowe novels, now known as The Misses Mallett, was originally called The Bridge Dividing. As characters in her books cross it, they cross from one aspect of their lives to another. Sometimes the land on the other side is a place of refuge, sometimes of danger, but there lies Monks’ Pool, based on Abbots Pool at Abbots Leigh. Whether the character is in turmoil, distressed or happy, the pool seems to represent peace and tranquillity – a place to gather their thoughts. Returning to Radstowe, real life comes rushing back.

On the Radstowe side of the bridge are the downs, with many viewpoints along the river. Here, from The Misses Mallett, is her description of the Avon Gorge, a scene almost unchanged even today:

‘Far below her was the river, flowing sluggishly in a deep ravine, formed on her right hand and as far as she could see by high grey cliffs. These for the most part were bare and sheer, but they gave way now and then to a gentler slope with a rich burden of trees, while, on the other side of the river, it was the rocks that seemed to encroach on the trees, for the wall of the gorge, almost to the water’s edge, was thick with woods.’

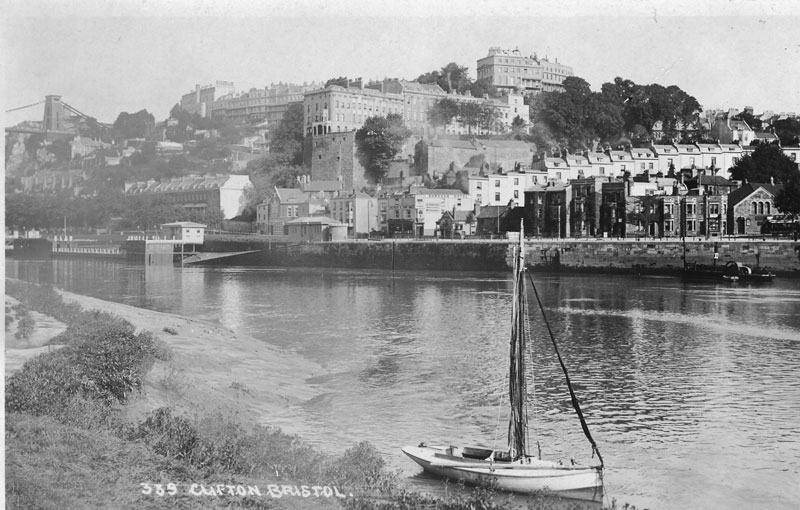

What has changed since her day are the docks. No longer are there ‘big ships with sacks of flour sliding into their holds, slow-moving cranes dangling their burdens with apparent unwillingness to let them go.’ The warehouses she describes have long gone or been turned to other uses, although there are still ferry boats and bridges. Yet such is her skill in describing these now vanished scenes that anyone who knows the area can for a moment imagine it revitalised, with the locks opening and closing as gulls wheel above the busy scene.

EH Young had an affection for the slightly faded glories of Clifton rather than the new houses on the other side of the downs. She preferred the fading squares with the ‘delicate tracery of the fanlights over the doors and the wrought iron balconies breaking the plain fronts’ even though most of the houses were in need of paint, and most of the rooms were let.

It is difficult to categorise the novels – they can hardly be described as romances, for love is often portrayed as destructive or an imprisonment. Young was a feminist, but she saw human failings in both men and women, and clearly admired strength of character.

Above all, the books are a celebration of Bristol, from its Edwardian times to the 1930s. Her last book, Chatterton Square, ends with the act of appeasement in Munich. It was written in 1947, when EH Young must have felt that the Bristol she knew had gone forever – and in some ways it had.

Today, the trams no longer rattle down Whiteladies Road. No more can one see ‘the masts and funnels of ships rising, as it seemed, from the street.’ Yet terraces still make up the Clifton streetscape. Alleyways and flights of worn steps still lead between Upper and Lower Radstowe, while even now, from above, the roofs below can be seen tumbling down the steep slopes ‘in every shape and colour … old red tiles in close neighbourhood to shining slates … mossy green roofs squeezed between the walls of higher houses .’ The downs still command a view of the gorge and the Zig Zag path still runs down to Hotwells. Above all, The Bridge still divides Upper Radstowe from the ‘innumerable possibilities on that farther side.’

EH Young and Ralph Henderson moved to Bradford on Avon after the death of his wife, and she died there in 1949. It is surely time for a revival of interest in her Radstowe books. Anyone who loves Bristol will love them, and there is plenty of detective work to do, figuring out which streets or squares were the models for those in fictional Radstowe.

• Visit akemanpress.com for more information